Understanding how computation works part 4

On this post, I will try to make you understand more about computer science. In this part of the post we are going to talk about Alan Turing machine, how it works and how can we simulate it.

On the last post, we’ve seen a little bit about “Pushdown finite automatas”, we’ve seen that it has more power than a finite automata because it has a thing called stack, if you don’t know what is a stack, just come back to the previous post. But, we’ve seen too that this stack has some inconveniences that limit us on how data can be used and stored.

To overcome those limitations, we are going to learn about a new machine, called deterministic Turing Machine. A Turing machine consists on a machine with a tape of unlimited length that can be read and write characters anywhere on it. The tape is serves as storage and input, and we can prefill it with a string of characters, during the execution the machine will read those characters and even replace them.

As usual in this post, we’re going to start using the deterministic machine, because as we saw on the last post, the deterministic constraints are always the better choice to have a fast machine.

As we’ve already seen, stacks can be read only by it top character, and you need to agree with me that this is too restrictive. Instead of using this type of stack, Turing made his machine with a thing called “tape head”, that serves as a writer/reader, and it can move left or right, giving more freedom to the machine, and taking off some limitations.

We this machine we could build a machine that increments a binary number, but to make the machine, we need to know how to increment this kind of number, let’s try to understand: If the digit is a zero, replace it with a one, if the digit is a one, replace it with a zero, then. increment the digit immediately to its left (“carry the one”) using the same technique.

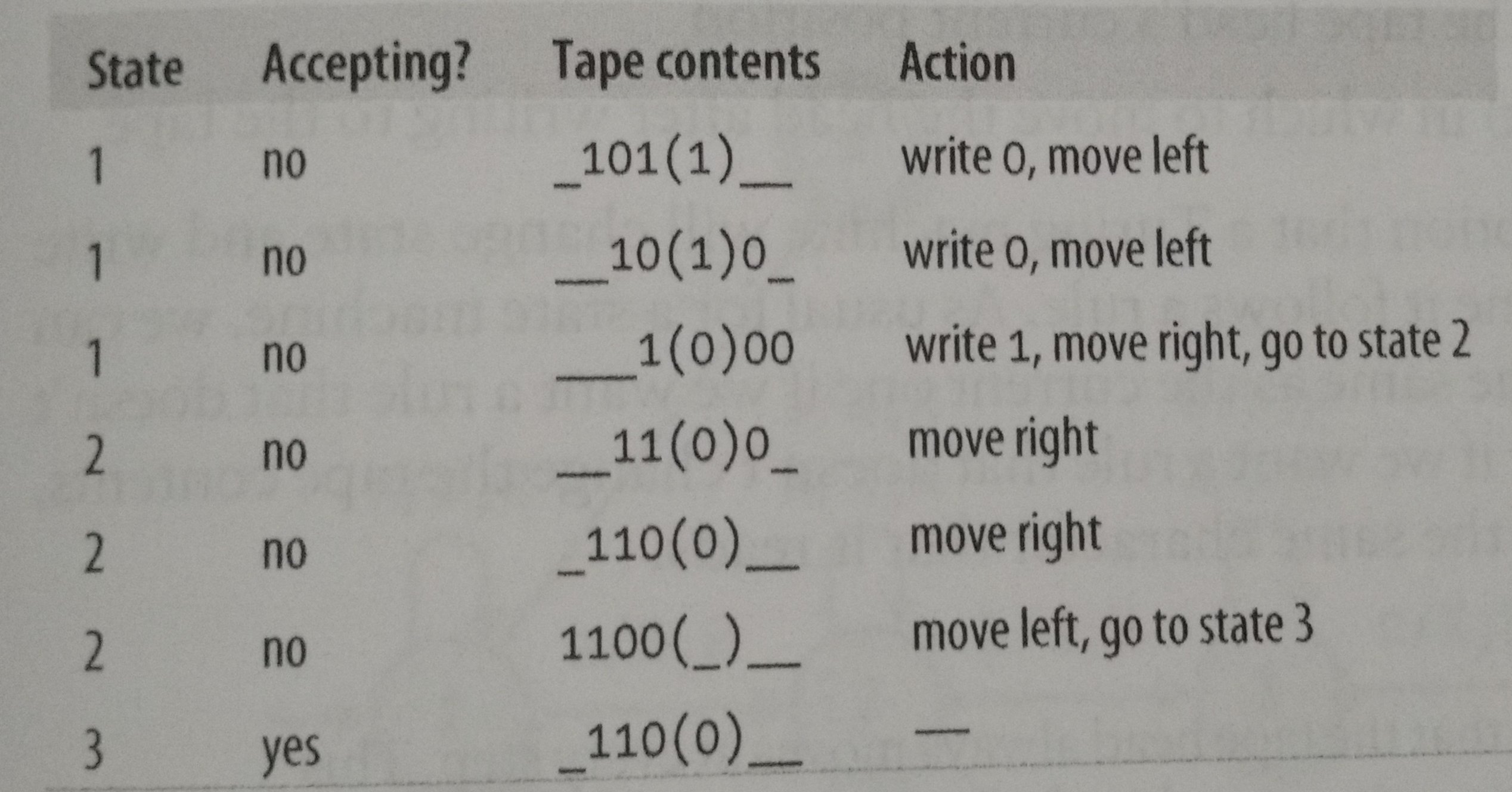

Now, let’s plan how the machine will work:

- Let’s give the machine 3 states, the third one will be the accept state.

- Start in state 1 with the tape head over the rightmost digit.

- When in state 1 and a 0 is read, overwrite it with a 1 and move to the state 2 and the tape head to the right.

- When in state 1 and a 1 is read, overwrite it with a 0 and move the tape head to the right.

- When in state 2 and a zero or a one is read, move the head right.

- When in state 2 and a blank is read, move the head to left and go into state 3.

So, look how the execution will be:

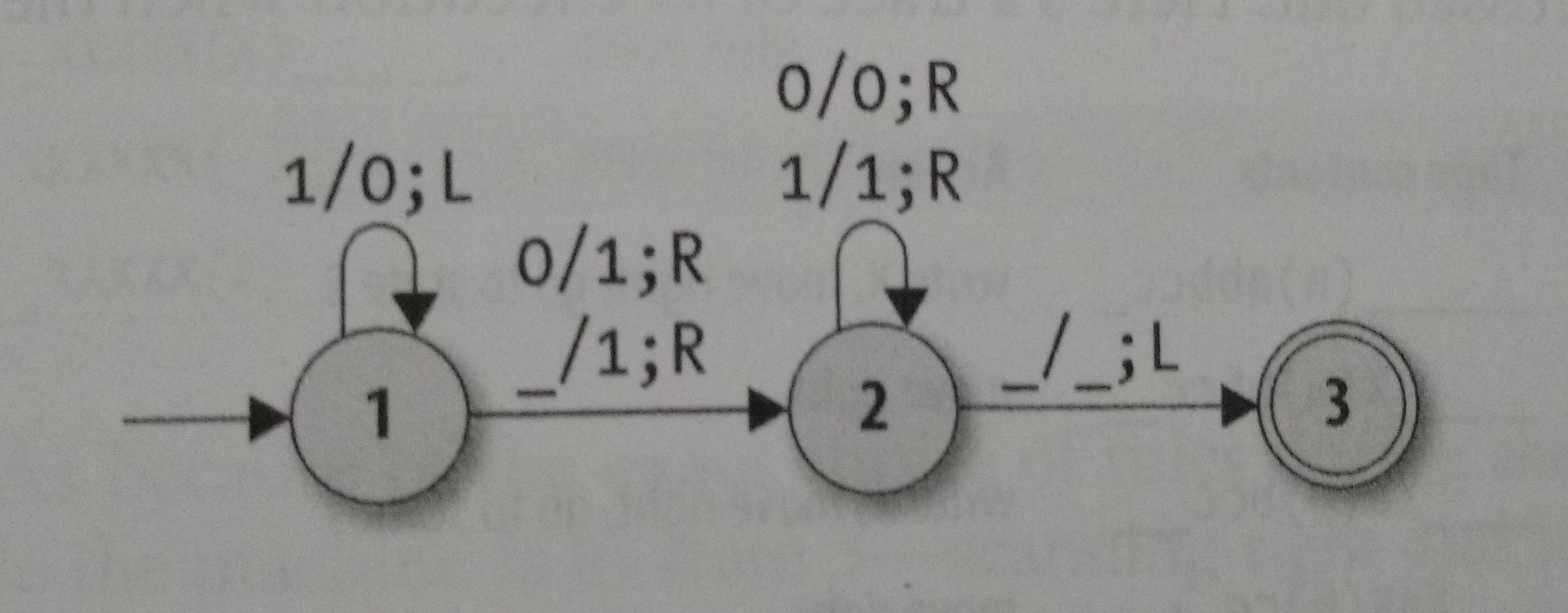

What about the rules, what will we need to make some rules? Obviously the current state and the next state, now, let’s think about the new tape, maybe the direction in which to move the head, also the character to write and the character to read on the current position. Well, I think we got it. So, how can we represent those rules in a diagram? Let’s look at this diagram below:

So, the first character is the one that need to be read, the second is the one the need to be write on the tape and the R/L that appears as the last information is the direction that the tape head need to move to.

Deterministic constraints in the Turing machine follows the same logic of the pushdown automata, we can follow the “no contradictions” constraint, but the “no omissions” is impossible, so we can keep with the stuck state for any eventual problem.

Let’s start to simulate this machine, the first step is the tape, how could we implement the tape? We need to divide the tape in three parts, the left side, the middle and the right side, and we must maintain the infiniteness of the tape, we can do it by using a blank everytime the head moves to a place without something written. Let’s implement it:

class Tape < Struct.new(:left, :middle, :right, :blank)

def inspect

"#<Tape #{left.join}(#{middle})#{right.join}>"

end

def write(character)

Tape.new(left, character, right, blank)

end

def move_head_left

Tape.new(left[0..-2], left.last || blank, [middle] + right, blank)

end

def move_head_right

Tape.new(left + [middle], right.first || blank, right.drop(1), blank)

end

end

Now, let’s test it working:

tape = Tape.new(['1', '0', '1'], '1', [], '_')

=> #<Tape 101(1)>

tape.middle

=> 1

tape.move_head_left

=> #<Tape 10(1)1>

tape.write('0')

=> #<Tape 101(0)>

Now that we have the tape working, we need to implement the configuration and the rules. Do you remember that we created a thing called Configuration, right? We’re going to use this, but instead of storing the stack in it, we’re going to store the tape.

class TMConfiguration < Struct.new(:state, :tape)

end

class TMRule < Struct.new(:state, :character, :next_state, :write_character, :direction)

def applies_to?(configuration)

state == configuration.state && character == configuration.tape.middle

end

def follow(configuration)

TMConfiguration.new(next_state, next_tape(configuration))

end

def next_tape(configuration)

written_tape = configuration.tape.write(write_character)

case direction

when :left

written_tape.move_head_left

when :right

written_tape.move_head_right

end

end

end

Now that we have a rule object, we can implemente the rulebook to list the rules and aplly them.

class DTMRulebook < Struct.new(:rules)

def next_configuration(configuration)

rule_for(configuration).follow(configuration)

end

def rule_for(configuration)

rules.detect { |rule| rule.applies_to?(configuration) }

end

end

Let’s wrap up all this up in a DTM class, we’re going to use the same methods “step” and “run” that we used on the small-steps machine.

class DTM < Struct.new(:current_configuration, :accept_states, :rulebook)

def accepting?

accept_states.include?(current_configuration.state)

end

def step

self.current_configuration = rulebook.next_configuration(current_configuration)

end

def run

step until accepting?

end

end

We are forgetting about the stuck state to handle the omissions, let’s implement it:

class DTMRulebook

def applies_to?(configuration)

!rule_for(configuration).nil?

end

end

class DTM

def stuck?

!accepting? && !rulebook.applies_to?(current_configuration)

end

def run

step until accepting? || stuck?

end

end

Now that we have a Deterministic Turing Machine implemented, let’s see it working:

tape = Tape.new(['1', '0', '1'], '1', [], '_')

=> #<struct Tape left=["1", "0", "1"], middle="1", right=[], blank="_">

rulebook = DTMRulebook.new([

TMRule.new(1, '0', 2, '1', :right),

TMRule.new(1, '1', 1, '0', :left),

TMRule.new(1, '_', 2, '1', :right),

TMRule.new(2, '0', 2, '0', :right),

TMRule.new(2, '1', 2, '1', :right),

TMRule.new(2, '_', 3, '_', :left)

])

=> #<struct DTMRulebook ...>

configuration = TMConfiguration.new(1, tape)

=> #<struct TMConfiguration state=1, tape=#<Tape 101(1)>>

configuration = rulebook.next_configuration(configuration)

=> #<struct TMConfiguration state=1, tape=#<Tape 10(1)0>>

configuration = rulebook.next_configuration(configuration)

=> #<struct TMConfiguration state=1, tape=#<Tape 1(0)00>>

dtm = DTM.new(TMConfiguration.new(1, tape), [3], rulebook)

=> #<struct DTM ...>

dtm.current_configuration

=> #<struct TMConfiguration state=1, tape=#<Tape 101(1)>>

dtm.accepting?

=> false

dtm.step; dtm.current_configuration

=> #<struct TMConfiguration state=1, tape=#<Tape 10(1)0>>

dtm.accepting?

=> false

dtm.run

=> nil

dtm.current_configuration

=> #<struct TMConfiguration state=3, tape=#<Tape 110(0)_>>

dtm.accepting?

=> true

So, as we’ve seen on finite automatas, we could convert the non-deterministic version into a deterministic one, because the deterministic could do everything that a non-deterministic machine do, the same apllies to the Turing machine, pushdown automatas are the only exception here. We can see also that giving a internal storage, a subroutine, multiple tapes or even a multidimensional tape won’t give the machine more power, that’s true because the task that the machine executes don’t need more of those thing to be done, those thing will only let it less complicated or faster, but this doesn’t mean more power.

Other thing we should discuss is about the machine purpose, we can see that all the automatas we’ve implemented were machines of single-purpose, implement a binary, recognize palindromes, accept strings, etc. So, how could we implement a general-purpose machine? We could describe a software on the tape of the Turing machine, and when the machine reads the description(rulebook, accept state, initial configuration), it would execute according to the description, we can call this machina a Universal Turing Machine(UTM), and we will try to implement it in the next post.

If you have any doubts about this post, talk with me on Facebook or Twitter