Understanding how computation works part 3

On this post, I will try to make you understand more about computer science. In this part of the post we are going to talk about a new type of automatas, called Pushdown Automata.

So, we learned what is automatas in the last post, we learned about the deterministic constraints and two type of Finite automatas: deterministic and non-deterministic.

As we see, just because a non-deterministic automata has more fancy thing, this doesn’t mean that it has more power than a deterministic automata, they have the same capability, and that’s why we could create a “NFA-to-DFA” object, converting a NFA into a DFA.

I would like to introduce you a new automata type, but first, I would like to give you an automata to create: imagine that we want to create a automata that is capable of reading opening and closing brackets, and it only accepts brackets that are balanced, so, how could you do it?

The strategy would be to keep tracking the nesting levels, for example, if we have “(())”, we have a bracket nested to another. Let’s see how it would look like:

So, let’s try to implement with the objects that we created in the last post:

rulebook = NFARulebook.new([

FARule.new(0, '(', 1),

FARule.new(1, '(', 2),

FARule.new(2, '(', 3),

FARule.new(1, ')', 0),

FARule.new(2, ')', 1),

FARule.new(3, ')', 2)

])

nfa_design = NFADesign.new(0, [0], rulebook)

nfa.accepts('(()')

=> false

nfa.accepts('(())')

=> true

nfa.accepts('(())()')

=> true

Looks like it is working, but…

nfa.accepts('((((((()))))))')

=> false

What is happening here is that, we aren’t covering all the nesting levels, and since our automata can only look until 3 levels, it doesn’t accept it. So, how could we implement something that works to all nesting levels? Now I can introduce you the new type of automata I mentioned before, and it is called Pushdown Automata.

A Pushdown Automata is a normal automata, that has a sort of external memory, called stack, a stack is a last-in first-out data structure that characters can be pushed and popped from it. A finite state machine like this is called a PDA(Pushdown automaton), and if it’s following the deterministic constraints, we can call it DPDA(Deterministic Pushdown Automaton). So, let’s start to think on a strategy to build a automata that accepts balanced brackets using DPDA:

- Let’s give the machine 2 states (1 and 2).

- State 1 will be our start state.

- When in state 1 and an opening bracket is read, push some character(b for brackets) onto the stack and move.

- When in state 2 and an opening bracket is read, push b onto the stack and stay at state 2.

- When in state 2 and an closing bracket is read, pop the character b off the stack and stay at state 2.

- When in state 2 and the stack is empty, move to state 1.

So, you can imagine that, the amount of b’s in the stack will be the number of nesting level of the brackets, right?

To implement the rules of a PDA you will need to have 5 things:

- Current state.

- Character that must be read from the input(optional).

- Next state.

- The character that must be popped off the stack.

- Sequence of characters that will be pushed onto the stack after the top character has been popped off.

The thing in PDA is that, you’re always going to pop the top character and then push some other characters onto the stack, every time it follows a rule. It’s a common practice to always start the stack with a dollar sign($), and let it there until the execution is over, if the stack has just the dollar sign, this means that it entered in a acceptance state.

This way, we can rewrite the balanced-bracket DPDA’s rules:

- When in state 1 and an opening bracket is read, pop the character ‘$’ and push ‘b$’, then, move to state 2.

- When in state 2 and an opening bracket is read, pop the character ‘b’ and push ‘bb’, then, stay on state 2.

- When in state 2 and an closing bracket is read, pop the character ‘b’ and push no characters, then, stay on state 2.

- When in state 2 and without read a character, pop the character ‘$’ and push ‘$’, then, move to state 1.

This is how it’s going to look like:

Each rule means: (input);(popped)/(pushed). But, I can imagine that you’re wondering that there is a “free move” in this automata, and this is a deterministic automata, so, something need to be explained.

The determinism constraints for PDA are the same: no contradictions or omissions, but, the way of thinking is different. We don’t have any contradiction in this automata since we don’t have any rule that have the same state and top-of-stack character as another rule, and the omissions is complicated because we would need to cover all the possibilities, and this is possible since the amount of possibilities with DPDA is huge. So, it’s conventional to just ignore this constraint of omission and allow DPDAs to specify only interesting rules that they need, and we could use a “stuck state” to be used when the automate find itself in a bad situation.

Now, I think we can start implementing some of our balanced-bracket DPDA, let’s start implementing an object for the stack:

class Stack < Struct.new(:contents)

def push (character)

Stack.new([character] + contents)

end

def pop

Stack.new(contents.drop(1))

end

def top

contents.first

end

def inspect

"#<Stack (#{top})#{contents.drop(1).join}>"

end

end

This way, we have a last-in first-out structure, let’s test it:

stack = Stack.new(['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e'])

=> #<struct Stack contents=["a", "b", "c", "d", "e"]>

stack.top

=> a

stack.pop.pop.top

=> c

stack.push('x').push('y').top

=> y

stack.push('x').push('y').pop.top

=> x

Now that we have the stack, we know that each PDARule will depend of two things: state and stack, so instead of speak about them separately, we could join them in one, and call it “Configuration”, and to implement it is very simple:

class PDAConfiguration < Struct.new(:state, :stack)

end

It will keep the state and the stack in one object. Now we need to implement the rules, but we need to remember that not only the state will say which rule to follow, but the whole configuration:

class PDARule < Struct.new(:state, :character, :next_state, :pop_character, :push_characters)

def applies_to?(configuration, character)

self.state == configuration.state &&

self.pop_character == configuration.stack.top &&

self.character == character

end

end

In pushdown automatas case, following a rule isn’t only changing the current state, but also to pop and push the stack, having this in mind, let’s implement the follow and next_stack methods:

class PDARule

def follow(configuration)

PDAConfiguration.new(next_state, next_stack(configuration))

end

def next_stack(configuration)

popped_stack = configuration.stack.pop

push_characters.reverse.inject(popped_stack) { |stack, character| stack.push(character) }

end

end

We need to reverse the push_characters because if we push characters onto a stack and then pop them of, they come out in the opposite side. Now that we have the rules, let’s try to implement the rulebook for the DPDA:

class DPDARulebook < Struct.new(:rules)

def next_configuration(configuration, character)

rule_for(configuration, character).follow(configuration)

end

def rule_for(configuration, character)

rules.detect { |rule| rule.applies_to?(configuration, character)}

end

end

This way, we can create the rulebook for the balanced-brackets DPDA:

rulebook = DPDARulebook.new([

PDARule.new(1, '(', 2, '$', ['b', '$']),

PDARule.new(2, '(', 2, 'b', ['b', 'b']),

PDARule.new(2, ')', 2, 'b', []),

PDARule.new(2, nil, 1, '$', ['$'])

])

Let’s save some energy and stop doing the whole DPDA manually, let’s implement the DPDA object, that builds a DPDA the way we want:

class DPDA < Struct.new(:current_configuration, :accept_states, :rulebook)

def accepting?

accept_states.include?(current_configuration.state)

end

def read_character(character)

self.current_configuration = rulebook.next_configuration(current_configuration, character)

end

def read_string(string)

string.chars.each do |character|

read_character(character)

end

end

end

Ok, now we can build a DPDA, feed it input and see when it accepts, but, we can see that we have one free move in the rulebook, so, we need to add a method to accept free moves on the rulebook class:

class DPDARulebook

def applies_to?(configuration, character)

!rule_for(configuration, character).nil?

end

def follow_free_moves(configuration)

if applies_to?(configuration, nil)

follow_free_moves(next_configuration(configuration, nil))

else

configuration

end

end

end

We need to support free moves in the DPDA object too, we could overwrite the current_configuration property, just making it follow the free move if it exists.

class DPDA

def current_configuration

rulebook.follow_free_moves(super)

end

end

As usual, let’s implement the DPDADesign, doing it we can check as many strings as we like:

class DPDADesign < Struct.new(:start_state, :bottom_character, :accept_states, :rulebook)

def accepts?(string)

to_dpda.tap { |dpda| dpda.read_string(string) }.accepting?

end

def to_dpda

start_stack = Stack.new([bottom_character])

start_configuration = PDAConfiguration(start_state, start_stack)

DPDA.new(start_configuration, accept_states, rulebook)

end

end

Let’s test what we have done until now:

dpda = DPDA.new(PDAConfiguration.new(1, Stack.new(['$'])), [1], rulebook)

=> #<struct DPDA ...>

dpda.read_string('(()('); dpda.accepting?

=> false

dpda.current_configuration

=> #<struct PDAConfiguration state=2, stack=#<Stack (b)bbb$ >

dpda.read_string('))()'); dpda.accepting?

=> true

dpda.current_configuration

=> #<struct PDAConfiguration state=1, stack=#<Stack ($) >

dpda_design = DPDADesign.new(1, '$', [1], rulebook)

=> #<struct DPDADesign ...>

dpda_design.accepts?('((((((()))))))')

=> true

dpda_design.accepts?('()(())((()))')

=> true

But, there is a problem in this implementation, if we try:

dpda.design.accepts?('())')

=> undefined method 'follow' for nil:NilClass (NoMethodError)

This happens because the next_configuration method assumes that it will always have a rule for all situation. To fix this, we are going to create a stuck state that since the automata gets there, it can’t move out.

class PDAConfiguration

STUCK_STATE = Object.new

def stuck

PDAConfiguration.new(STUCK_STATE, stack)

end

def stuck?

state == STUCK_STATE

end

end

class DPDA

def next_configuration(character)

if rulebook.applies_to?(current_configuration, character)

rulebook.next_configuration(current_configuration, character)

else

current_configuration.stuck

end

end

def read_character(character)

self.current_configuration = next_configuration(character)

end

def read_string(string)

string.chars.each do |character|

read_character(character) unless stuck?

end

end

def stuck?

current_configuration.stuck?

end

end

Using the new stuck state, it returns:

dpda = DPDA.new(PDAConfiguration.new(1, Stack.new(['$'])), [1], rulebook)

=> #<struct DPDA ...>

dpda.read_string('())'); dpda.current_configuration

=> #<struct PDAConfiguration state=#

Okay, now we finished the Deterministic part, let’s start to talk about the Non-deterministic automata, we can see that this automata that we implemented (balanced-brackets) is just using the stack to check if the stack is empty or not, but we could use stack for more than this, for example we can create a automata that accepts a string with equal amounts of a’s and b’s, like this:

This automata is quite similar to the balanced-brackets machine, but it stack is more used to check the amount of a’s and b’s, but even this automata isn’t taking full advantage of the stack. One way of taking more advantage of the stack is building a machine that accepts palindromes. Look this example:

We can see that this DPDA accepts palindromes, but with a ‘m’ separating the reverse part from the normal part since we can’t build a DPDA that recognizes when to stop pushing to the stack. How could we make a machine that accepts palindrome without this ‘m’?

We can use the Non-deterministic constraints, using a free move that allows the automata to change states whenever it thinks it is necessary. Look how it would look like:

So, let’s try to implement the Non-deterministic pushdown automata, let’s start with the rulebook:

require "set"

class NPDARulebook < Struct.new(:rules)

def next_configurations(configuration, character)

configuration.flat_map { |config| follow_rules_for(config, character) }.to_set

end

def follow_rules_for(configuration, character)

rules_for(configuration, chracter).map { |rule| rule.follow(configuration) }

end

def rules_for(configuration, character)

rules.select { |rule| rule.applies_to?(configuration, character) }

end

end

</code>

As we could see on the last Non-deterministic automata we implemented that we used Sets to keep track of the state possibilities, but now we need to keep track of the configuration possibilities.

Now, let’s implement a method to support the free moves:

class NPDARulebook

def follow_free_moves(configurations)

more_configurations = next_configurations(configurations, nil)

if more_configurations.subset?(configurations)

configurations

else

follow_free_moves(configurations + more_configurations)

end

end

end

Let’s wrap up a rulebook with the current Set of configurations by creating a object NPDA:

class NPDA < Struct.new(:current_configurations, :accept_states, :rulebook)

def accepting?

current_configurations.any? { |config| accept_states.include?(config.state) }

end

def read_character(character) self.current_configurations = rulebook.next_configurations(current_configurations, character) end

def read_string(string) string.chars.each { |character| read_character(character) } end

def current_configurations rulebook.follow_free_moves(super) end end </code>

And to test strings directly:

class NPDADesign < Struct.new(:start_state, :bottom_character, :accept_states, :rulebook)

def accepts?(string)

to_npda.tap { |npda| npda.read_string(string) }.accepting?

end

def to_npda

start_stack = Stack.new([bottom_character])

start_configuration = PDAConfiguration.new(start_state, start_stack)

NPDA.new(Set[start_configuration], accept_states, rulebook)

end

end

So, let’s test the palindrome machine and see how ours object are working:

rulebook = NPDARulebook.new ([

PDARule.new(1, 'a', 1, '$', ['a', '$']),

PDARule.new(1, 'a', 1, 'a', ['a', 'a']),

PDARule.new(1, 'a', 1, 'b', ['a', 'b']),

PDARule.new(1, 'b', 1, '$', ['b', '&']),

PDARule.new(1, 'b', 1, 'a', ['b', 'a']),

PDARule.new(1, 'b', 1, 'b', [['b', 'b']]),

PDARule.new(1, nil, 2, '$', ['&']),

PDARule.new(1, nil, 2, 'a', ['a']),

PDARule.new(1, nil, 2, 'b', ['b']),

PDARule.new(2, 'a', 2, 'a', []),

PDARule.new(2, 'b', 2, 'b', []),

PDARule.new(2, nil, 3, '$', ['$']),

])

#<struct NPDARulebook ...>

configuration = PDAConfiguration.new(1, Stack.new(['$']))

=> #<struct PDAConfiguration state=1, stack=#<Stack ($) >

npda = NPDA.new(Set[configuration], [3], rulebook)

=> #<struct NPDA ...>

npda.accepting?

=> false

npda.current_configurations

=> #<Set: {#<struct PDAConfiguration state=1, stack=#<Stack ($) >, #<struct PDAConfiguration state=2, stack=#<Stack (&) >}>

npda.read_string('abb'); npda.accepting?

=> false

npda.current_configurations

=> #<Set: {#<struct PDAConfiguration state=1, stack=#<Stack (["b", "b"])a$ >, #<struct PDAConfiguration state=2, stack=#<Stack (a)$ >}>

npda.read_string('a'); npda.accepting?

=> true

npda.current_configurations

=> #<Set: {#<struct PDAConfiguration state=2, stack=#<Stack ($) >, #<struct PDAConfiguration state=3, stack=#<Stack ($) >}>

npda_design = NPDADesign.new(1, '$', [3], rulebook)

=> #<struct NPDADesign ...>

npda_design.accepts?('abba')

=> true

npda_design.accepts?('babbaabbab')

=> true

npda_design.accepts?('abb')

=> false

So, in the first type of automata, we saw that we could convert a Non-deterministic automata into a deterministic one, but this isn’t possible with PDA’s, since we now use a stack, we can’t implement every possibilities of stack into a single stack to simulate a DPDA as we did with states in the NFA-to-DFA algorithm, it’s impossible. We could prove this non-equivalence simply using the unmarked palindrome problem that we had, we couldn’t build a DPDA that can accept only palindrome without something marking its middle.

As we saw in the previous post, we used automatas to implement regular expressions, with the extra stack power we can parse programming languages. In the first post we parsed SIMPLE, that it was a programming language we created. Treetop use a single parsing expression grammar to describe the complete syntax of the language, this is a modern idea, a traditional way is to break the parsing process in two: Lexical analysis and Syntactic analysis.

The lexical analysis consists in reading a raw string and turn it into a sequence of tokens, and the syntactic analysis consists in read the sequence of tokens that the lexical analysis produced and decide whether they represent a valid program according to the syntactic grammar of the language being parsed. Let’s try to parse SIMPLE, and to achieve this, we are going to start by the lexical analysis:

class LexicalAnalyzer < Struct.new(:string)

GRAMMAR = [

{token: 'i', pattern: /if/ },

{token: 'e', pattern: /else/ },

{token: 'w', pattern: /while/ },

{token: 'd', pattern: /do-nothing/ },

{token: '(', pattern: /\(/ },

{token: ')', pattern: /\)/ },

{token: '{', pattern: /\{/ },

{token: '}', pattern: /\ }/ },

{token: ';', pattern: /\;/ },

{token: '=', pattern: /\=/ },

{token: '+', pattern: /\+/ },

{token: '*', pattern: /\*/ },

{token: '<', pattern: /</ },

{token: 'n', pattern: /[0-9]+/ },

{token: 'b', pattern: /true|false/ },

{token: 'v', pattern: /[a-z]+/ }

]

def analyze

[].tap do |tokens|

while more_tokens?

tokens.push(next_tokens)

end

end

end

def more_tokens?

!string.empty?

end

def next_tokens

rule, match = rule_matching(string)

self.string = string_afeter(match)

rule[:token]

end

def rule_matching(string)

matches = GRAMMAR.map {|rule| match_at_beginning(rule[:pattern], string) }

rules_with_matches = GRAMMAR.zip(matches).reject { |rule, match| match.nil? }

rule_with_longest_match(rules_with_matches)

end

def match_at_beginning(pattern, string)

/\A##{pattern}/.match(string)

end

def rule_with_longest_match(rules_with_matches)

rules_with_matches.max_by { |rule, match| match.to_s.length }

end

def string_after(match)

match.post_match.lstrip

end

end

And we can see that it returns the tokens when I call “analyze” method:

LexicalAnalyzer.new('y = x * 7').analyze

=> ["v", "=", "v", "*", "n"]

As we can see, the lexical analysis is very easy, let’s start the harder part, that’s to decide if the sequence of tokens we receive is syntactically valid for SIMPLE. First of all, we need to make a syntactic grammar that describes how tokens may be combined:

This is called the context-free grammar, each rule has a symbol on the left and one or more symbols and rokes on the right. We can apply the grammar rules to recursively expand symbols until only tokes remain. Look an example:

Now, let’s understand how this technique works:

- We need to pick a character for each symbol, to distinguish from the tokens, we are going to use uppercase characters.

- Let’s use the stack from the PDA to represent the grammar symbols and tokens. When the PDA starts, we need to have one symbol pushed onto the stack to represent the structure we are trying to parse:

start_rule = PDARule.new(1, nil, 2, '$', ['S', '$']) - Let’s implement each PDA following the syntactic grammar, each rule will describe how to expand a single symbol into a sequence of symbols and tokens:

symbol_rules = [<statement> ::= <while> | <assign>

PDARule.new(2, nil, 2, ‘S’, [‘W’]), PDARule.new(2, nil, 2, ‘S’, [‘A’]),

<while> ::= ‘w’ ‘(‘ <expression> ‘)’ ‘{‘ <assign> ‘}’

PDARule.new(2, nil, 2, ‘W’, [‘w’, ‘(‘, ‘E’, ‘)’, ‘{‘, ‘S’, ‘}’]),

<assign> ::= ‘v’ = <expression>

PDARule.new(2, nil, 2, ‘A’, [‘v’, ‘=’, ‘E’]),

<expression> ::= <less-than>

PDARule.new(2, nil, 2, ‘E’, [‘L’]),

<less_than> ::= <multiply> ‘<’ <less-than> | <multiply>

PDARule.new(2, nil, 2, ‘L’, [‘M’, ‘<’, ‘L’]), PDARule.new(2, nil, 2, ‘L’, [‘M’]),

<multiply> ::= <term> ‘<’ <multiply> | <term>

PDARule.new(2, nil, 2, ‘M’, [‘T’, ‘*’, ‘M’]), PDARule.new(2, nil, 2, ‘M’, [‘T’]),

<term> ::= ‘n’ | ‘v’

PDARule.new(2, nil, 2, ‘T’, [‘n’]), PDARule.new(2, nil, 2, ‘T’, [‘v’]) ] </code>

- Let’s give each toke character a PDA rue that reads that character from the input and pops it off the stack, since it doesn’t have use to the syntactic analysis:

token_rules = LexicalAnalyzer::GRAMMAR.map do |rule| PDARule.new(2, rule[:token], 2, rule[:token], []) end - And finally, when the stack is empty, just move to an accept state:

stop_rule = PDARule.new(2, nil, 3, '$', ['$'])

Now we can analyze if a statement is valid or not to SIMPLE:

rulebook = NPDARulebook.new([start_rule, stop_rule] + symbol_rules + token_rules)

=> #<struct NPDARulebook ...>

npda_design = NPDADesign.new(1, '$', [3], rulebook)

=> #<struct NPDADesign ...>

token_string = LexicalAnalyzer.new('while ( x < 5 ) { x = x * 3 }').analyze.join

=> "w(v<n){v=v*n}"

npda_design.accepts?(token_string)

true

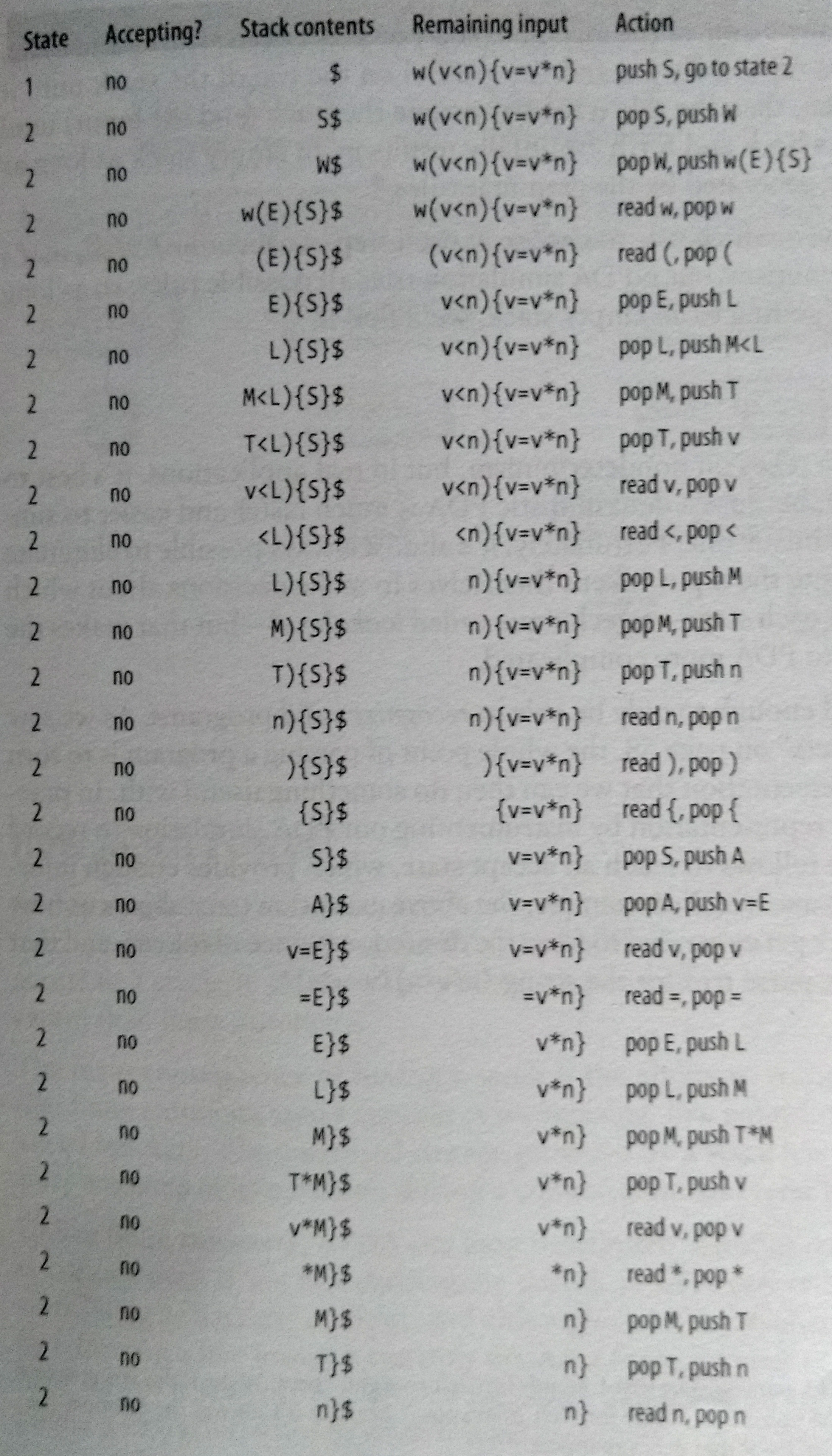

Look the step by step of this process:

We made this application using nondeterministic, but in real application it is better to avoid it since deterministic PDA are faster and easier to simulate.

If you have any doubts about this post, talk with me on Facebook or Twitter